Land art as colonial practice

A written report on Claiming land for art, claiming land through art (September 17, 2024) by Anne Louïse van den Dool, and a aftermovie by Beeldkrakers

What do land art and colonialism have to do with each other? More than you might think. This became clear during the hybrid meeting Claiming land for art, claiming land through art on Sept. 17, 2024 at the University of Amsterdam, as part of the pre-program of the international conference Land Art Lives. Experts from home and abroad chimed in to make the connection between land art and land seizure.

The meeting was opened by Martine van Kampen, curator of Land Art Flevoland, which has ten land art works in the Dutch polder under its care. Ever since the emergence of the land art movement in the 1970s, questions have been raised about the colonial dimension of this type of art, she explains in her introduction. After all, an artist appropriates a piece of land, seemingly unaware of the history and functions of these square meters or even kilometers.

One of the questions that recurs frequently during this meeting is whether this reasoning also applies to the works of art in Flevoland. After all, these were not built on pre-existing land, but on land reclaimed by man's own hand. Nevertheless, the colonial dimension of land art is not entirely absent in this province either, it becomes clear in the course of the discussion: the reclaimed area where Flevoland is now to be found also has a long history, recognized by some land art artists more than others. Moreover, the Dutch history of land reclamation is closely linked to colonial history: Dutch engineers were already constructing polders in Suriname and Indonesia to optimize the efficiency of plantations and land reclamation.

Presentation Emily Eliza Scott

The meeting's first guest speaker is Emily Eliza Scott, assistant professor of History of Art and Architecture and Environmental Studies at the University of Oregon and co-author of the book Critical Landscapes: Art, Space, Politics, who connects via video link from the United States. She encourages attendees to interpret the term land art as broadly as possible: polders can also be understood as land art. The same goes for landscape parks in America: these are often seen primarily as natural areas, but are actually heavily influenced by humans. Where national parks were resurrected over the centuries, indigenous peoples had to give way, or they were made part of the tourist's supposedly authentic experience with staged rituals.

This example fits well with a misconception that is also common in the development of land art: that of a piece of land as a tabula rasa, not yet claimed by anyone and certainly not inhabited. Often enough, these thoughts do not match reality at all. Nonetheless, landscape artists appropriate such pieces of land by creating barriers with their works, for example in the form of artificial embankments and furrows, which divide or even brutally slice the land.

Finger on the sore spot

Some works of land art actually bring this colonial dimension into focus. A telling example is Nicholas Galanin's Never Forget from 2021, in which the famous Hollywood letters in Los Angeles have been recreated, but now with the text “Indian Land,” to make it clear that another people originally lived on the site of Hollywood. This colonial aspect also appears regularly in the work of Imani Jacqueline Brown, as in If toxic air is a monument for slavery, how do we tear it down, where she shows on maps how air pollution and the appropriation of land are related.

This last example in particular raises the question of whether this is land art, but that does not, according to Scott, limit the possibilities for meaningful reflection on how ownership of the earth's surface is distributed. Through these works, too, creators of land art can be made aware of the effects that their works, however well-intentioned, can bring about.

[text continues below photos]

Awareness of history, presentation by Hanneke Stuit

Next to speak is Hanneke Stuit, associate professor of Literary and Cultural Analysis at the University of Amsterdam and affiliated with the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA). She knows the surroundings of the Flevoland land artworks well: she grew up in this province, although as a child she gave little thought to the fact that she actually lived at the bottom of the sea. Only when she later delved into the history of this reclaimed piece of land did she realize that this land had been dry before: there was no sea here in 500 BC.

Not everyone seems to know about this - not even landscape artists. Daniel Libeskind, for example, with Polderland Garden of Love and Fire (1997), part of the collection of Land Art Flevoland, refers to the location of this artwork as a place without history. With this work he attempts to add that history: the work consists of five lines, each referring to a place in the world that does carry that history, such as Salamanca, Berlin and Amsterdam. However, the preference for these locations is highly personal: Libeskind chose them because they are significant to him, including as the location of his studio and as the birthplace of one of his favorite authors.

This line of thought shows little awareness of the history that is already present at the location of the artwork, and to which the name Almere - the name of the lake that lay in the Middle Ages where the IJsselmeer is now found - even refers. According to Stuit, it would be more appropriate to add at least one more line, which follows the original polder landscape, thus calling attention to everything that is already present at this spot.

Colonies of Weldadigheid

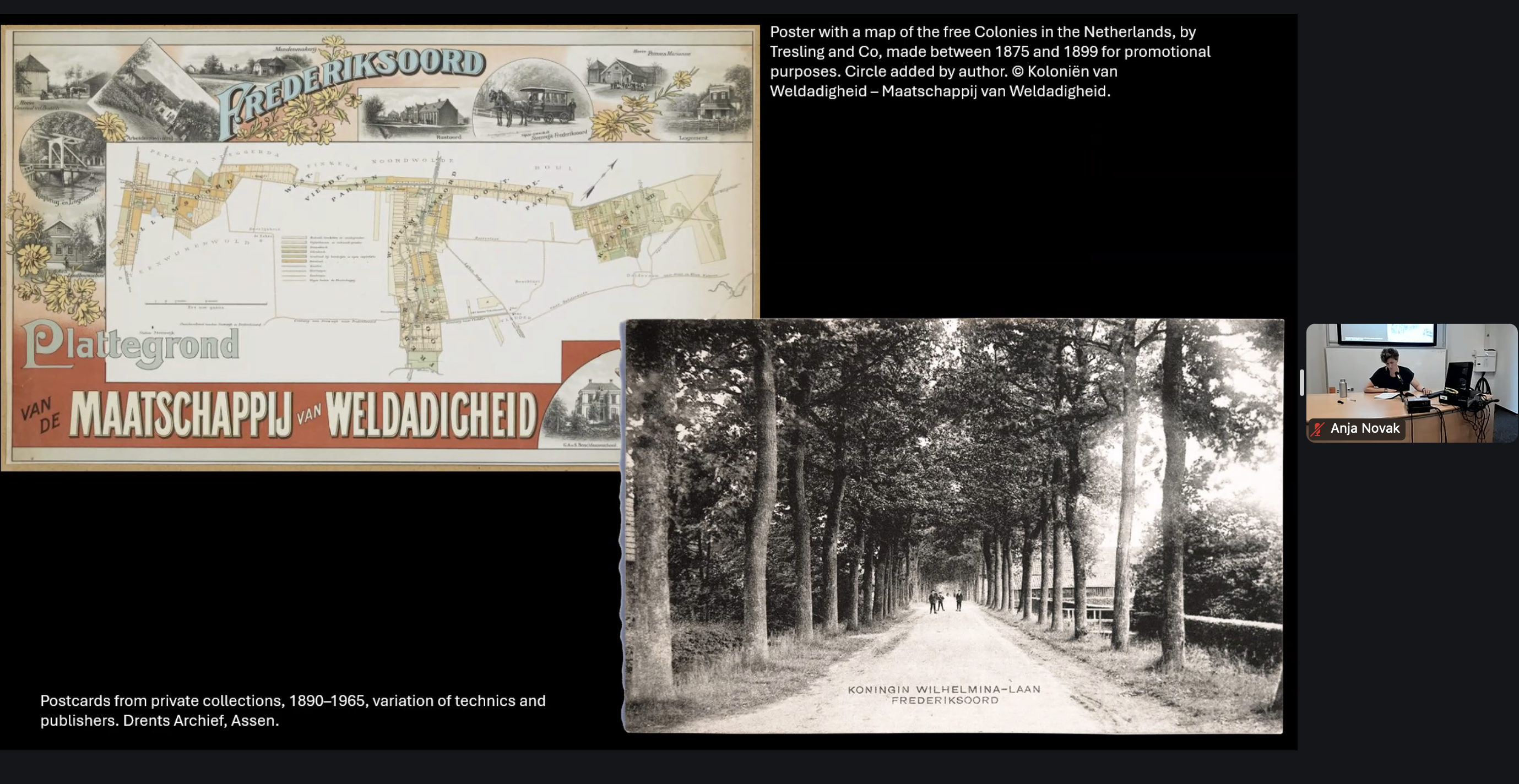

Like Scott, Stuit cites an example of landscape editing that not everyone would immediately label as land art, but which intervenes in a similar way in the existing landscape, without accounting too much for previous functions. Stuit takes a closer look at the Colonies of Weldadigheid, some seven complexes scattered throughout the Netherlands and Belgium that were established in 1818 to instill labor morality in poor people.

In their design, the sites are reminiscent of the plantations in the former colonies: they are vast, geometrically straight fields with ditto paths, allowing the residents to be kept in sight at all times. Communal facilities were placed in the middle so that everyone could reach them as quickly as possible.

The Colonies of Weldadigheid looked eye-catching in their symmetry, but practice was different. The message toward the outside world was that poor people were offered a chance for a meaningful existence here, but in fact systematic oppression and mistreatment took place, cultivating the land for their own gain.

The same could equally be said about the way the countryside on which these complexes were built were appropriated. No thought seemed to be given to the functions that the land had previously occupied, and took these square miles in colonial fashion, propagating that in this way value was only added and rather than taken away.

Questioning and breaking down boundaries

Not every land art artist takes this approach, Stuit emphasizes. A good example is Deltawerk // (2018) by RAAAF and Atelier de Lyon in Marknesse, also part of Land Art Flevoland's collection. This work is a transformed version of the Delta flume, one of the models used to test the Delta Works, among other things. Large blocks from the concrete walls have been sawn, turned and tilted. Over the years, nature will take over the artwork, and mosses and ferns will take possession of it. Deltawerk // is thus not only a monument to that struggle and ingenuity in the field of water management, but also raises questions about the pursuit of an indestructible Netherlands in a time of climate change and rising sea levels.

Deltawerk // shows how land art works can also question or even break down man-made boundaries. Such art is gaining relevance today as more and more people become aware of the knock-on effects of colonial practices of the past and the impact of human actions on the earth, including in the form of rising sea levels on the one hand and extreme drought on the other. Attendees at Claiming land for art, claiming land through art were at least deeply aware of this, thanks in part to the enlightening talks by both speakers.