Reflection on a sold-out first international conference on the future of Land Art

Conference report Land Art Lives 2024, written by Anne Louïse van den Dool, the aftermovie by Beeldkrakers and the integral video recordings of the presentations by Vidépro.

On 3 October 2024, Land Art Lives held its first international conference on the future of land art at the Agora Theatre in Lelystad. The day opened with presentations from a range of international speakers, followed by breakout sessions that explored varied perspectives on land art's evolving future. Alongside this inspiring program, participants had ample opportunities for networking and delving into curated reading and archival materials.

Morning programme

Land Art lives. This was clearly evident on 3 October at Land Art Lives, where over two hundred artists, policymakers, and enthusiasts from the Netherlands and abroad gathered to exchange insights and find inspiration for the future of land art. As the first international conference dedicated to the subject, it featured a rich program of lectures, discussions, and workshops, all ably chaired by Meta Knol.

The conference is the culmination of an extensive program on the future of land art, which included thoughtful reflection on the colonial dimensions and heritage aspects of land art. This initiative is a collaboration between Kunstmuseum M., represented by program maker Anne Reenders, and Land Art Flevoland, represented by curator Martine van Kampen. Prior to Land Art Lives, they embarked on a joint journey across the United States, visiting sites like the Noah Purifoy Desert Art Museum near Los Angeles and iconic works such as Sun Tunnels (1973–1976) by Nancy Holt and Spiral Jetty (1970) by Robert Smithson near Salt Lake City, Utah.

Looking to the future, there is a clear need for a broader, more inclusive perspective than the current, often conventional image dominated by male, white artists making bold interventions in the landscape. Equally vital is a climate-focused approach: how can land art prompt reflection on our relationship with nature and the profound changes it is undergoing? Finally, the audience for land art is also considered: how can these works engage and resonate with new audiences?

Nature and culture intertwined

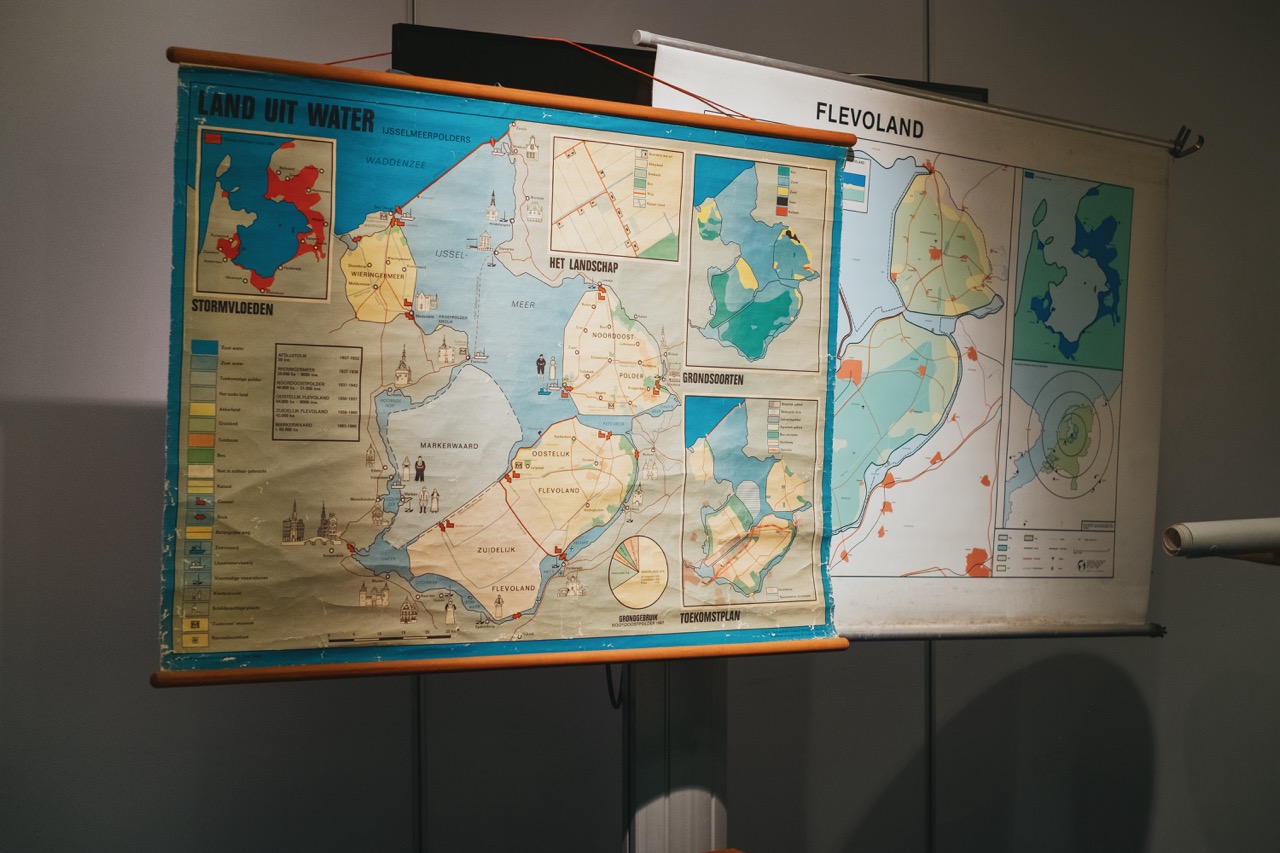

Also in attendance were several local and provincial politicians from the area: Sjaak Kruis, alderman of Lelystad; Sjaak Simonse, member of the Flevoland provincial executive; and Paul Tang, alderman of Almere. Each highlighted the distinctiveness of the conference location: with ten works, Flevoland boasts the largest collection of land art in the Netherlands and, as a province shaped by human hands, it might even be considered a work of land art in its own right. Safeguarding this unique fusion of nature and culture for the future is essential, including by continuing to maintain the works, enhancing accessibility, and increasing awareness of this collection, among other efforts.

Taking the floor, Van Kampen and Reenders express their hope that this conference will lay the foundation for a lasting international knowledge platform dedicated to land art. But what exactly is land art? There is no definitive answer, they emphasize. The term encompasses various synonyms and a wide range of materials—from cement to wood, from film to sound. What is certain, however, is that this art movement has existed for over 50 years and is practiced by artists all over the world. It can be viewed as a significant impulse that influenced numerous other art movements and should, as such, definitely not be underestimated.

Land Art Lives was recorded in full, watch the 1st of four videos here:

Humberto Moro: Land Art within and beyond museum walls

After an introductory overview of the pre-program, the day transitions to the keynote sessions. Humberto Moro, Deputy Program Director of the Dia Art Foundation in New York, opens with a discussion on the various ways art and land intersect. The iconic land art works managed by the Dia Art Foundation in the United States, such as Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty (1970) and Walter De Maria's The Lightning Field (1977), serve as prime examples.

In his lecture, Moro illustrates how land art not only brings art out of the museum but also, conversely, invites natural materials into the museum galleries. While it is not always easy to preserve and present such works in the context for which they were created, this remains the enduring goal, whether indoors or outdoors. Take Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973–1976), for instance: their interaction with Utah's vast desert landscape, where the rising and setting sun shines through the openings in the massive tubes, forms the essence of the work. The same applies to Delcy Morelos' El abrazo (2023), exhibited within the spaces of Dia: a walkable installation made of clay and straw that envelops visitors, giving them the sensation of being embraced by the earth. This experience is heightened by the use of strongly scented herbs and spices, such as cinnamon and cloves.

Time and place

Such grand and complex projects are only made possible through collaborations with partners like the Holt/Smithson Foundation, as well as with local communities, Moro emphasizes. These partnerships are crucial in preserving a form of art deeply connected to the question of land ownership and belonging. It highlights the importance of understanding the history of the land beneath our feet—an especially crucial awareness in a country like the United States, where land ownership and rights remain contentious issues. In this way, Moro argues, land art is not just about place but, crucially, about time.

Introduction and follow-up discussion with Anja Novak (University of Amsterdam)

Following his lecture, Anja Novak, Associate Professor of Contemporary Art at the University of Amsterdam, engages Moro in a discussion about the commonalities with Flevoland. Similar challenges in land art conservation are present there, particularly concerning the ten artworks in Land Art Flevoland's collection. Created over the past 50 years, these works continuously require care and preservation. Moreover, they draw attention to the question of ownership: who has the rightful claim to this land, reclaimed by human hands?

Land Art Lives was recorded in full, watch Humberto Moro's presentation and the conversation with Anja Novak here:

Land Art in the Ruhr region

Next, Britta Peters, Artistic Director of Urbane Künste Ruhr in Germany, takes the stage. Since 2018, she has been managing projects that deepen the relationship between art and public space. In her talk, she shares numerous examples of art in public spaces managed by Urbane Künste Ruhr, with a special focus on the industrial and urban contexts where these works are situated.

Peters illustrates that public art does not need to retain its original form forever, however much these environments seem to invite it. In her lecture, she addresses the concept of time in both practical and philosophical terms. The passing of time causes existing artworks to transform into new forms, for instance, through the reuse of their materials. In this way, these artworks reveal that time never stands still and that the world around us—even if not immediately visible—is constantly changing, for instance, as a result of climate change.

Following this, Lisa Le Feuvre, Executive Director of the Holt/Smithson Foundation in the United States, joins the discussion.Together, they reflect, among other things, on the significance of the infrastructure in the Ruhr region—not only in terms of mobility, but also in relation to the various local political, social, and societal dynamics shaped by this environment.

Land Art Lives is recorded in full, watch the presentation Britta Peters and the conversation with Lisa Le Feuvre:

Interactive afternoon program

The afternoon program begins with five breakout sessions led by Reframing Studio, with support from experts from the Netherlands and abroad, including representatives from the Cultural Heritage Agency RCE, the Kröller-Müller Museum, Stroom Den Haag, and the IJssel Biennale. Energized by the morning’s keynote lectures and the outcomes of the pre-program, attendees engage in workshops to discuss the future of land art. The goal is to gather input and inspiration for shaping future land art policies in Flevoland and across the Netherlands.

In the various rooms of the Agora Theatre, attendees gather in groups to discuss pressing questions. How can a land art collection be more aligned with the present? How can the stewardship of land art incorporate new insights from the heritage sector? How can we find and engage an audience for land art? And how can we gather relevant knowledge about land art while sustaining the exchange of information? The five groups in each of the breakout sessions work to answer these questions, collaboratively crafting a new narrative about the future of land art in smaller teams.

Each participant is assigned a role, such as tour guide, word artist, vibes manager, or time saver. Additionally, each team includes representatives for both the country and the arts, ensuring their interests are also considered. By gathering aspirations for the future, a collective dream emerges, which is presented at the end of the day to the deputy for culture of the province of Flevoland, who appears deeply impressed.

Ongoing discussion

At the end of the day, all attendees gather in the theatre auditorium to share the collected narratives. A strong desire emerges to give a voice to nature or the land itself, whether in poetic or other forms: a nature that calls for attention to its own needs and, at times, even asks to be left undisturbed, contrary to human desires. At the same time, it is suggested that land art can play a role—both now and in the future—in fostering conversations about current social issues, such as climate change and colonialism. The overarching message, as organizers Martine van Kampen and Anne Reenders emphasize in their closing remarks, is that the potential forms and impact of land art in the coming decades are too diverse to be captured within a single narrative.

It underscores the importance of maintaining an ongoing conversation about land art and its future—precisely what Land Art Lives aspires to achieve with its international knowledge center dedicated to land art.

Who attended Land Art Lives?

Marlous van Boldrik: 'I teach post-war art at an American university. Many land art artists hail from the United States, but there is also an impressive collection of land art in Flevoland that I would love to show my students.'

Niels Albers: ‘I create architectural interventions, including for TU Delft. I want to develop my work further in the direction of land art, so when I saw this conference, I knew I had to attend.’

Anne Croft: ‘I recently graduated in urban planning from the University of Amsterdam. I enjoy learning more about land art and the future of this movement, especially in relation to climate change. I am convinced that land art can reach a wide audience and, as a result, make a significant impact.’

Riccardo Venturi: ‘I am a French-Italian art historian and critic. In 2021, I visited Robert Smithson’s Broken Circle/Spiral Hill in Emmen—a unique opportunity, as the work is not normally open to visitors. Since then, it has continued to fascinate me, also because it is Smithson’s only work in Europe.’